04/09/96 - 11:20 AM ET - Click reload often for latest version

Each week, USA TODAY will feature a leading college coach providing

tips on improving hockey skills. This week's guest coach is Larry

Pedrie of the University of Illinois at Chicago.

How to play a one-on-one rush

by Coach Larry Pedrie, University of Illinois at Chicago

A difficult skill for a young defenseman (or forward if he happens

to be caught temporarily in the defenseman's position) to learn

is defending a one-on-one rush. Although there are many things

that come into play in developing this skill, there are four basic

principles I believe will greatly enhance success in this situation.

- The first principle to be learned is very simple, however

it is often overlooked and not executed. In defending the one-on-one,

the defender must always keep his or her stick on the ice. That's

it. But as simple as that is, quite often the young player doesn't

remember to do this. Frequently, the defender in a one-on-one

will put his or her stick in two hands at the waist. The reasons

to follow this principle are:

- It helps to control positioning of the forward by offering

less ice for the forward to work with. The forward cannot carry

the puck into ice that is occupied by the defender's stick.

- It forces the forward to make his decision four-to-six feet

sooner. By having the defender's stick on the ice and adding the

length of the stick to the length of the defender's arm (without

extending the arm), this distance adds up to somewhere between

four-to-six feet away from the defender's body. This forces the

forward into the confrontation sooner. If the stick is carried

in two hands at the waist, the forward can then take advantage

of that extra space and carry the puck right into the defender's

feet.

- It puts the defender in a position to pokecheck the puck away

from the forward. It is difficult to pokecheck when the stick

is carried at the waist.

- It puts the defender in a position to block or deflect passes.

When the stick is in the air, it is very difficult to interfere

with the shot or a pass to a second rushing attacker.

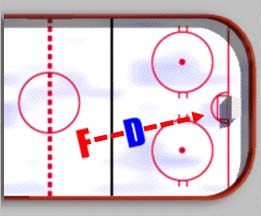

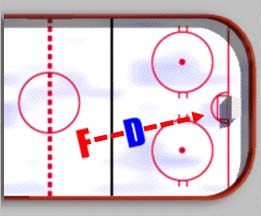

- The second principle to successfully defending a one-on-one

is holding the middle of the ice in all one-on-one situations

(see diagram above). If the defender maintains the middle or inside

position on the attacking forward, one of two things will happen:

- The forward will choose to go outside, which now puts the

defender at a huge advantage toward winning the one-on-one. The

attacker's path to the net is now much further than the defender's.

Or . . .

- The forward will choose to go inside, which should bring the

confrontation directly into ice covered by the defender, given

proper gap control (principle No. 4), allowing the defender to

win the one-on-one.

- A second way of understanding holding the middle is to always

be certain that the attacker's direct path to the net should always

go through the defender. The defender should never align shoulder

to shoulder with the attacker (unless the attacker is in the exact

middle of the ice). A good gauge would be for the defender to

align the outside shoulder with the attacker's inside shoulder.

This alignment takes away the forward's direct path to the net

and encourages him or her to go outside where he or she is less

likely to become dangerous.

- The third principle is even simpler than the first one: Make

sure that you do not fish! This means be certain not to play the

puck. If the defender chooses to play the puck and not the man,

chances of winning the one-on-one are greatly reduced. This does

not mean the defender shouldn't pokecheck. It means he or she

does not focus their eyesight and put 100% concentration on the

pokecheck. The defender should attempt the pokecheck without looking

down at the puck. The focus needs to be on the attacker's body.

However, playing the body does not mean hitting the attacker.

While it was formerly thought that hitting the attacker was the

way to play a one-on-one, it is now believed that this is incorrect.

The defender's positioning has to be perfect in a one-on-one to

initiate body contact. Trying to force a hit in all situations

causes lunging, which usually equals failure in the one-on-one

situation. Holding the middle and no fishing is far more important

than hitting in learning to play the one-on-one rush.

- The fourth and most difficult principle is learning and maintaining

proper "gap control." This involves both skating skills

and intelligence. It requires a defender to be fairly adept at

backwards skating. Once a player skates well backwards, the thinking

aspect comes into play. The defender must gauge the attacker's

forward skating speed against his own backward skating speed.

The defender must attempt, by adjusting his or her speed, to be

a short distance, five to 10 feet, from the attacking forward

as the play nears the defensive blueline. Once inside the blueline,

space between the attacker and the defender should continue to

be lessened by the defender. As the play reaches the top of the

circles, the gap should be closed and the confrontation should

occur. However, it's important to remember that the confrontation

should not occur by the defender lunging to make a hit. The confrontation

should be a result of the attacker entering the space occupied

by the defender as the attacker attempts to reach the net.

If these four basic principles can be learned and executed, a

young player will have success defending a one-on-one situation.

Larry Pedrie is in his sixth season as the coach of the University

of Illinois at Chicago Flames program. Pedrie has developed the

reputation of building his teams around a strong defensive-style

of hockey, a philosophy that dates back to his playing day at

Ferris State University. The 36-year-old native of Detroit was

a four-year letterwinner with the FSU Bulldogs from 1978-81. In

1981, Pedrie graduated with a bachelor's degree in business management

and an associate degree in business accounting. Following graduation,

he became an assistant coach at his alma mater (1982-84), then

three years later became an assistant at UIC (1985-87). In 1987,

he accepted an assistant's position at the University of Michigan

under coach Red Berenson, where he stayed until taking over the

UIC program in the summer of 1990.